This is part of the ongoing Jackpot Chronicles, looking at four possible Coronavirus scenarios or lenses.

The last instalment was “Force Majeure”, which posited a complete breakdown in seemingly permanent institutions. As it may turn out, these outwardly immovable edifices may not survive this economic collapse and be left out of “the new normal” that emerges out the other end.

Given that the idea of Coronavirus being concocted in a Wuhan Lab has gone from being a conspiracy theory that could get you deplatformed, to being seriously looked into by Western intelligence agencies, now may be a good time to look at the “Tin Foil Hat” scenario, and try to discern where viewing this pandemic through the proverbial conspiracy theory lens actually gets us.

Conspiracy theories make for tricky subject matter for anybody who tries to look deeper than the veneer of conventional narratives. What we are expected to accept unquestioningly out of mainstream circles is sometimes less plausible than what we are expected to dismiss as conspiracy theories.

It get’s even more distorted when inversions or backwardations occur between what is fringe and what is, ostensibly, “fact”.

Russiagate was a conspiracy theory, one that was platformed as common knowledge by multiple mainstream media outlets for over two years before finally being conceded as a nothingburger by the Mueller Report. There are still people walking around believing that the current US president was installed as a Manchurian candidate by the Kremlin, and you’re the one in the tin-foil hat for pointing out how disconnected from reality that actually is.

I’ve been very clear about this all along. Russia hacked 2016 in advance, and changed vote totals by deleting registrations. But it was NOT enough to put Trump over the top. Without Comey’s last minute letter, Trump would have lost. This is very, very simple.

— Palmer Report (@PalmerReport) May 15, 2019

(somwhere along the line, legendary usenet kook alt.genius.bill-palmer got himself a blue check)

This is typical of the hall of mirrors you enter when trying to understand the dynamics of conspiracy theories. Even the term “Conspiracy Theory” is itself the subject of conspiracy theories. The legend goes that the term was invented by the CIA to marginalize pesky truthers (another loaded word) that were finding all kinds of holes in the official explanation of the JFK assassination.

Whether it’s the implausibility of a “magic bullet” in Dealey Plaza or what many building engineers and pilots have to say about 9/11, the official explanatory cover for such world-changing events are so riddled with inconsistencies and flaws that they can only be believed by those who do not examine them.

The danger in admitting to oneself that at least some aspects of the most pivotal events of our era are not what they seem, is that it can pull you into a downward spiral where everything becomes a conspiracy and nothing is as it seems.

We all know somebody who thinks every news story, every event that occurs is a direct outcome of some shadowy cabal that controlled the event, manipulated the circumstances that precipitated it, and selected the outcome to serve their own agenda.

This is not to say that people and groups don’t conspire, that societal elites don’t have a self-serving agenda and that moral hazard and pathological opportunism do not play a significant role in outcomes. In essence, that’s politics. But here’s the crucial duality of conspiracy theory:

To the degree that all major events being manipulated behind the scenes by hidden conspirators is actually impossible, so to is the degree to which the mainstream media explanations of events are mostly inaccurate and at times infantile.

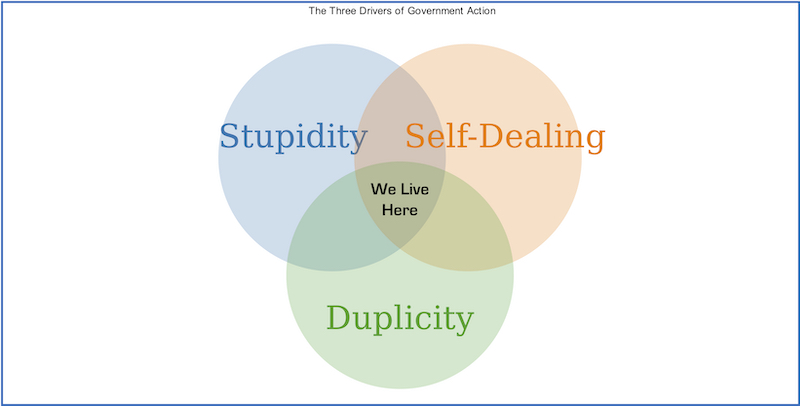

Into this milieu, enter the tin-foil-hats, and things become inordinately more precarious. What we get is a type of three-body-problem writ large where the three independent narrative forces can be described by three age-old adages, ( all of which are possibly apocryphal quotes):

- “Never ascribe to conspiracy what can be explained by stupidity” (a.k.a Hanlon’s Razor, often attributed to Napoleon Bonaparte)

- “Never let a good crisis go to waste” (Winston Churchill)

- “Never believe anything until it is officially denied” (Bismarck)

The outcomes we as citizens experience, subject to our leaders following varying degrees of these three impulses can be rendered in a Venn diagram with three drivers: Stupidity, self-dealing and duplicity.

As I’ve been exploring a lot lately, we live in something that increasingly resembles a cyberpunk bizarroverse. One where the explanatory powers of mainstream media are in secular decline and in which our institutions have largely discredited themselves. Two powerful coping mechanisms are:

1) to pretend nothing is wrong and that business as usual can continue even though the underlying scaffolding of the system is imploding (hypernormalisation)

2) subscribe to some non-sanctioned narrative that purports to reconcile the discrepancy between what we believe should be happening with what we are actually experiencing.

For my part, I find the most useful components of both conspiracies and consensus is that they are both known to provide an explanation of events that I can reliably assume as having near zero accuracy. A useful concept for this came out of Douglas Adams’s Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy. In it his concept of the recipriversexcluson describes a number whose value can be only be defined as anything but itself. Whatever the expert consensus is saying is happening or will happen, that’s the one outcome you do not need to plan for. Same goes for most conspiracies.

Introducing the Gell Mann Amnesia Effect

The last idea I’ll introduce is that mainstream media has itself, become a type of conspiracy theory. There is less reporting, less actual journalism and mostly punditry and editorializing. Ben Hunt gives us the concept he calls The Gell Mann Amnesia Effect (the phenomenon was originally described by Michael Crichton):

“Briefly stated, the Gell-Mann Amnesia effect is as follows. You open the newspaper to an article on some subject you know well. In Murray’s case, physics. In mine, show business. You read the article and see the journalist has absolutely no understanding of either the facts or the issues. Often, the article is so wrong it actually presents the story backward—reversing cause and effect. I call these the “wet streets cause rain” stories. Paper’s full of them.

In any case, you read with exasperation or amusement the multiple errors in a story, and then turn the page to national or international affairs, and read as if the rest of the newspaper was somehow more accurate about Palestine than the baloney you just read. You turn the page, and forget what you know.”

I noticed this phenomenon years ago, but didn’t have a name for it. In my case, most articles I read in the mainstream press about the domain name system, DNS, and naming in general are so bad as to be cringeworthy. This is one of my faves:

Applying all this to Coronavirus narratives, we can look at what a specific narrative says is or will happen, what it probably preludes from happening.

So when experts say we may have to be on lockdown for 2 years, I assume it’ll come in lower.

When some authority says we we will never shake hands again, I don’t bank on it.

When people on Youtube say 5G causes Coronavirus, I’m pretty sure it doesn’t.

When they say the virus was engineered and released deliberately to bring about a totalitarian police state, I think that gives too much credit to the people who run governments (see Venn diagram).

So where does all this get us?

Enter Radical Uncertainty.

This is the title of Mervyn King and John Kay’s latest book. King was the Governor of the Bank of England from 2003 to 2013 and presided over the Global Financial Crisis, writing about his experience in his previous book The End of Alchemy. Kay is an economist who held various positions in academia (former Dean, Oxford Business School, also London School of Economics) and author of Other People’s Money.

Their central theme is that many problems we face are inherently unknowable and that no amount of data or sophisticated modelling is going to get us anywhere near a reliable probability of what any of it means, or what will happen.

Radical uncertainty cannot be described in the probabilistic terms applicable to a game of chance. It is not just that we do not know what will happen. We often do not even know the kinds of things that might happen. When we describe radical uncertainty we are not talking about ‘long tails’ — imaginable and well-defined events whose low probability can be estimated, such as a long losing streak at roulette. And we are not only talking about the ‘black swans’ identified by Nassim Nicholas Taleb — surprising events which no one could have anticipated until they happen, although these ‘black swans’ are examples of radical uncertainty.‘?

We are emphasizing the vast range of possibilities that lie in between the world of unlikely events which can nevertheless be described with the aid of probability distributions, and the world of the unimaginable. This is a world of uncertain futures and unpredictable consequences, about which there is necessary speculation and inevitable disagreement — disagreement which often will never be resolved. And it is that world which we mostly encounter.

So the ramifications of radical uncertainty go well beyond financial markets; they extend to individual and collective decisions, as well as economic and political ones; and from decisions of global significance taken by statesmen to everyday decisions taken by the readers of this book.

Radical Uncertainty means gearing our efforts toward coherently responding to events as opposed to insisting on modelling them with an eye toward achieving optimal outcomes, be that “full employment”, a targeted inflation rate or the elimination of the business cycle.

“Governments choose policies to maximise social welfare. A moment’s introspection is enough to tell us that they don’t. They could not conceivably have the information required to do so. They do not know all the available options, and they are uncertain what the consequences of them will be. They do not even know whether what they wish for today will be what they still want if they achieve it tomorrow….the notion that a government could calculate what maximises social welfare is simply ridiculous. The consequences of policies and actions are far too uncertain….”

It is arguable that many of the problems we experience today, such as debt bubbles and brittle supply-chains are the result of trying to prevent bad outcomes of the past instead of facing them head on and taking the requisite pain when they happened (no bailouts, allowing the over-leveraged to fail). But they didn’t and this is a major reason why the pandemic, when it finally hit, is having such a disastrous effect for something that all else considered, isn’t as deadly as pandemics of the past.

Ironically, Radical Uncertainty was written just before the outbreak, it’s publication date was March 17, just as things were really coming unglued…

“The Black Death will not recur – plague is easily cured by antibiotics (although the effectiveness of antibiotics is under threat) – and a significant outbreak of cholera in a developed country is highly unlikely. But we must expect to be hit by an epidemic of an infectious disease resulting from a virus which does not yet exist. To describe catastrophic pandemics, or environmental disasters, or nuclear annihilation, or our subjection to robots, in terms of probabilities is to mislead ourselves and others. We can talk only in terms of stories. And when our world ends, it will likely be the result not of some ‘long tail’ event arising from a low-probability outcome from a known frequency distribution, nor even of one of the contingencies hypothesised by Martin Rees and colleagues, but as a result of some contingency we have failed even to imagine.”

So as I try to balance out these varying imperfect narratives from mainstream sources, official sources, and the tin foil hats, I try to use them more as filters to identify what to take out of the equation than as providing information and having explanatory power.

-

I eliminate what the prominent futurists and experts say will happen

-

I eliminate the reason why conspiracists say something is happening

-

I severely discount what the MSM says is happening.

Then I look at what’s left and try to make sense of it. To that end while I personally think that all most of the hysterical outcomes, in terms of millions of deaths, mandatory implants, FEMA camps, are highly improbable, under the Jackpot’s Tin Foil Hat Scenario I’d be wrong (think China, everywhere).

What I am positioning for is a mother of all economic depressions, rampant inflation, joblessness, war on cash and basically everything described in the second part of Graham Summers’s The Everything Bubble (tl/dr Inflation, NIRP, War on Cash, Bail Ins and wealth taxes). When I run through all of this filtering and analysis this is what looks more imminently probable to me.

While I don’t think of these anticipated events in terms of a coordinated global conspiracy to screw all the plebes (again, consult the Venn diagram), I do expect that the rationalizations of these events along with the narratives justifying them will be rife with conspiracy-sounding elements. This brings us back to the hall-of-mirrors aspect of what is conspiracy versus what Jaques Ellul called “integrative propaganda” in such times as these.

For the next edition of The Jackpot Chronicles I decided to rename the “Mandatory Pollyanna” scenario. That’s the one where central planners and bureaucrats manage to “save” the economy yet again. However the cost of that would be to undertake an LBO of the entire economy and running it as a centrally planned utility. I’ve decided to rename that one “The Great Bifurcation”, after the the inevitable result of that would be emergence of an even more pronounced and starkly divided Two Tier Society.

To get alerted when the next edition comes out or to get on the list in general, sign up here, or follow me on Twitter here.